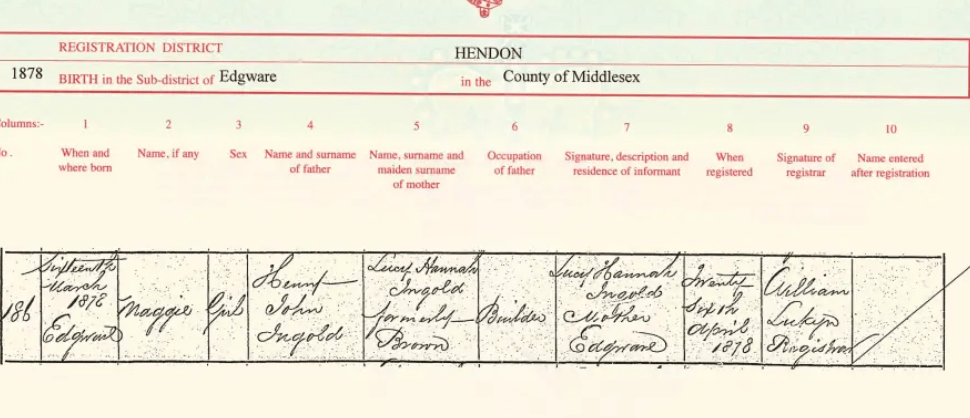

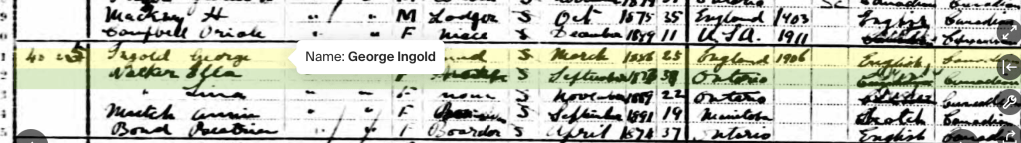

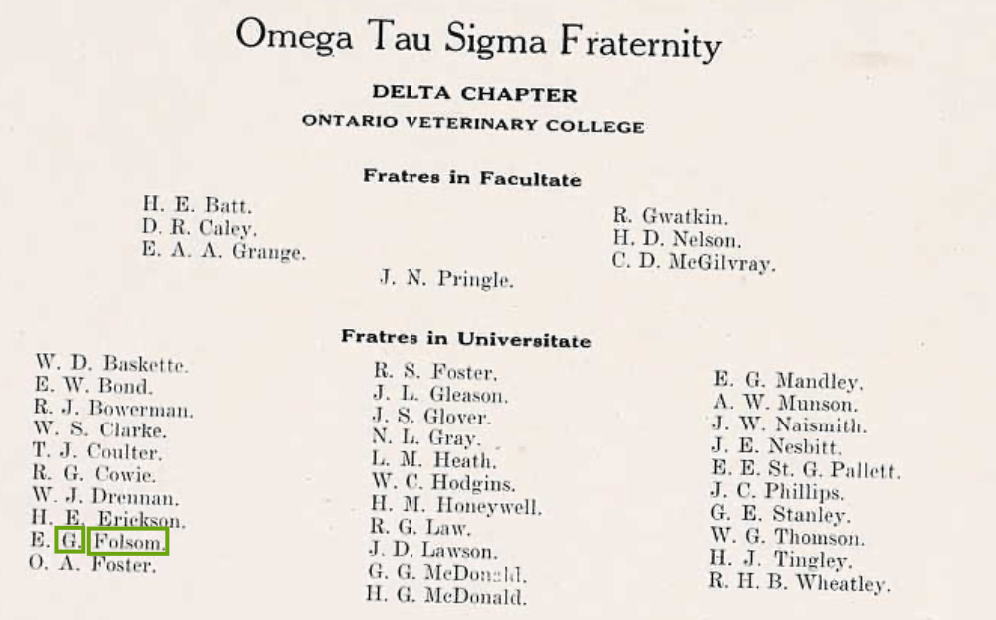

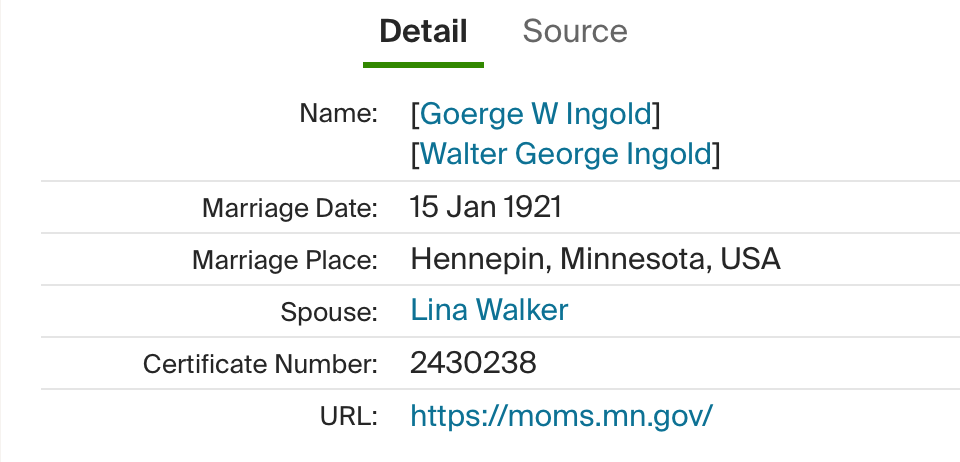

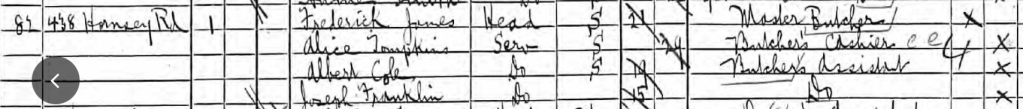

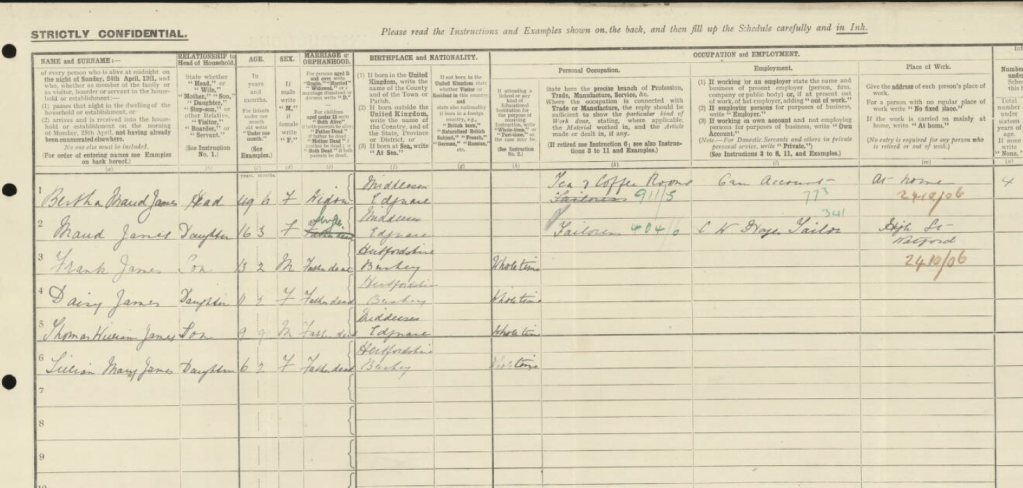

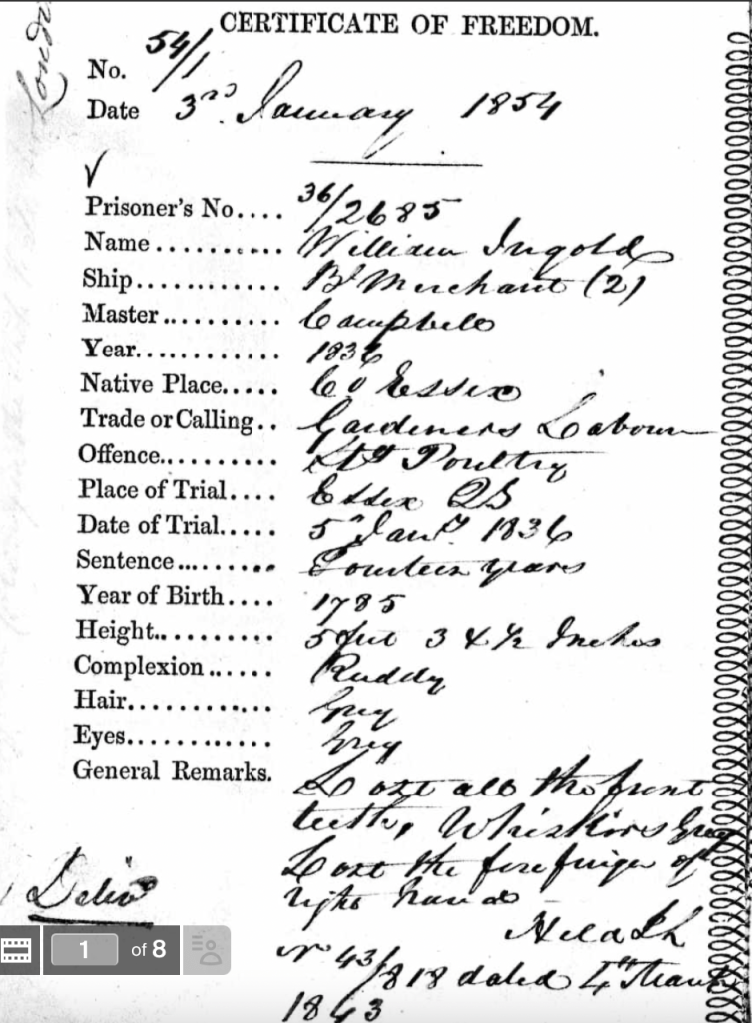

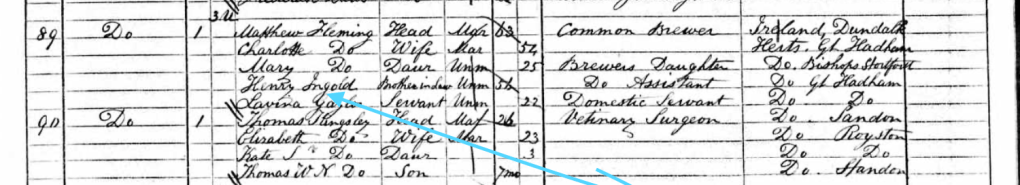

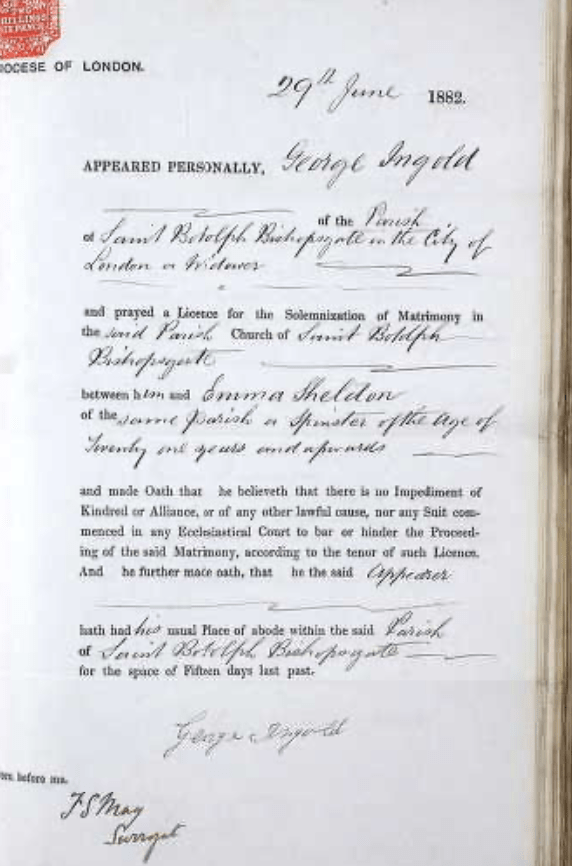

The long lost brother of Walter (George) Ingold

b. Sept19.1879 Edgware UK d. Aug14.1945 East London South Africa,

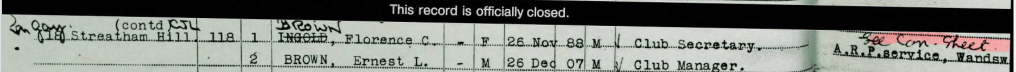

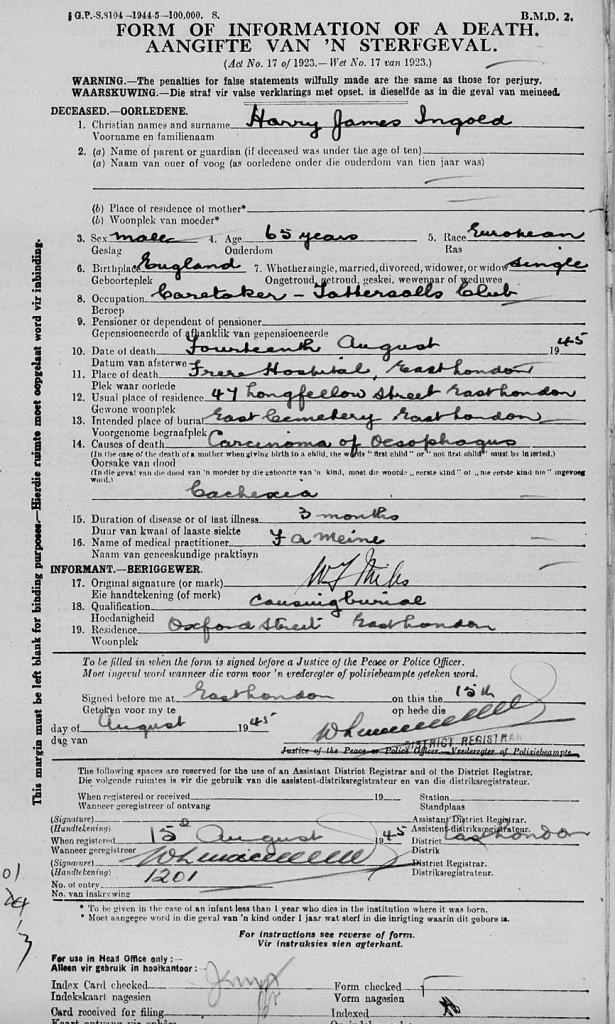

On August 14, 1945, Harry James Ingold died alone at Frere Hospital in East London, East Cape, South Africa. The cause of death was “carcinoma of the esophagus”, and “cachexia” – a kind of anorexia related to cancer. He was 65 years old. Occupation: “Caretaker at Tattersalls Club”.

The only thing my father knew about his Uncle Harry James Ingold was “he went to South Africa to look for diamonds and the family never heard from him again”.

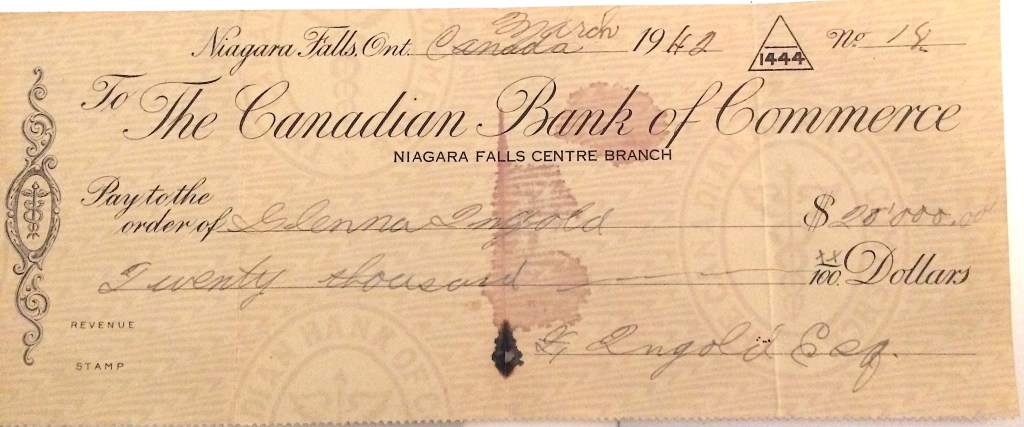

In 2017 we found an interesting item in my late Aunt Glenna’s belongings: an uncashed cheque payable to her for $20,000 dated March, 1942, signed by “H. Ingold, Esq”. It was drawn on my grandfather’s George’s local bank account, but surely he was pranking his kids with tales of a rich uncle in South Africa.

It got me wondering what actually became of Harry after he went to East Cape.

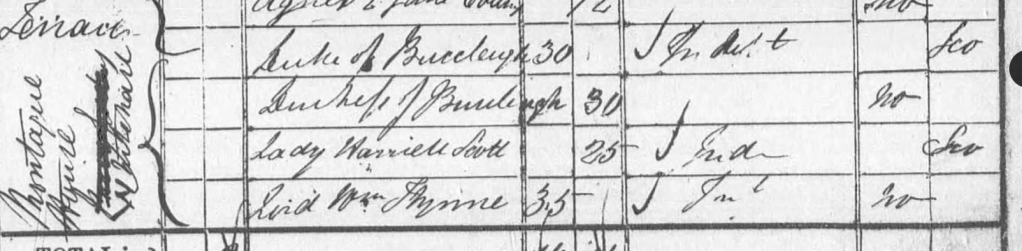

Below: The Steamship Goorkha

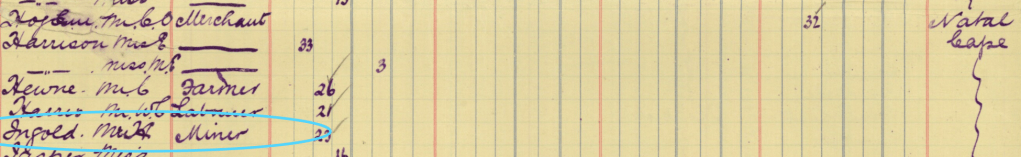

Below: Harry Ingold’s manifest entry. The voyage took 42 days!

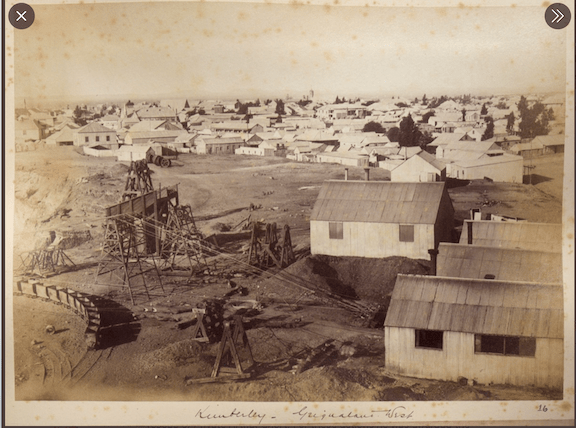

The Kimberley Mine, Northern Cape, South Africa

If Harry actually arrived at or worked as a miner at Kimberley, it’s certain he didn’t stay long. An egregious example of colonialism, the Kimberley Mine was rampant with disease and violence. The abuse of black workers was horrific. Only the De Beers family profited, otherwise it was a place to die. Kimberley even had it’s own cemetery.

Below: Kimberley Mine, 1900

Below: Kimberley Mine today – one of South Africa’s top tourist attractions

Cape Town and Service in The Boer War – 1901

In 1901 Harry was living in Observatory, a suburb of Cape Town. He lived on Station Road in Albany Park.

Below: Station Road, 1901

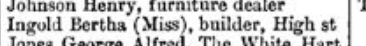

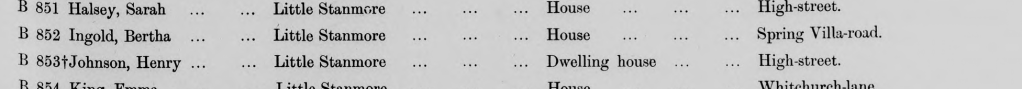

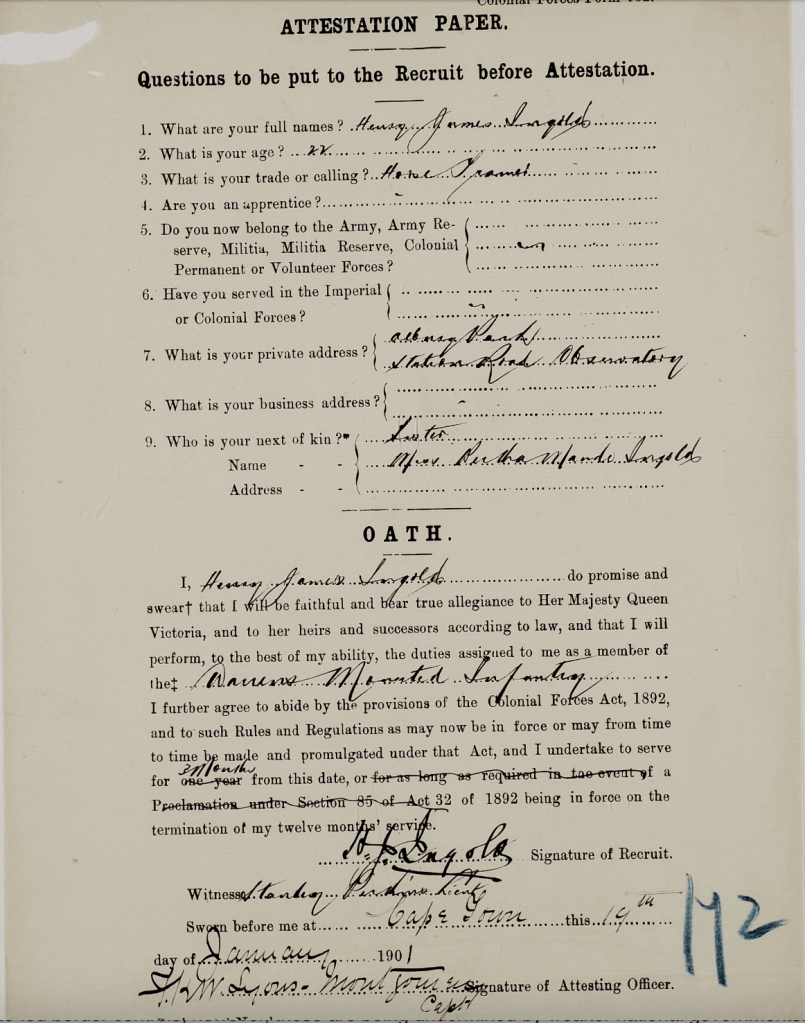

On January 19, 1901, he walked into Drill Hall at Cape Town to answer a call for militia men for “Warren’s Mounted Infantry”. His attestation lists his occupation as “horse trainer”. He was unmarried at the time, naming his next of kin as his eldest sister, Bertha Maud Ingold.

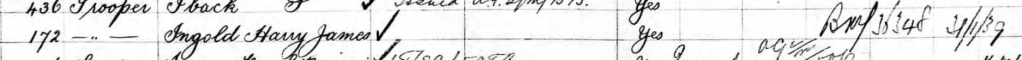

Warren’s Mounted Infantry played an unremarkable role in the Boer War. Harry served as a Trooper from April to August of 1901.

Below: Standard Kit for Mounted Infantry and Warren’s Mounted Infantry Uniform Badge

Later Life

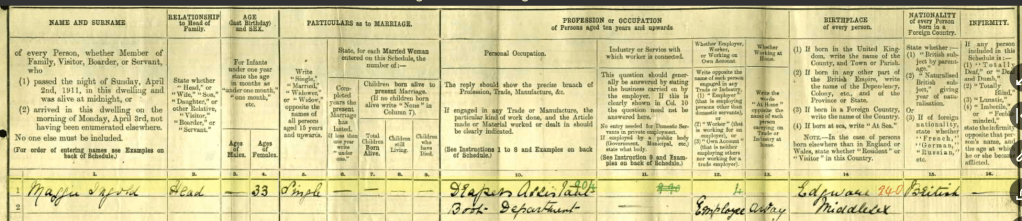

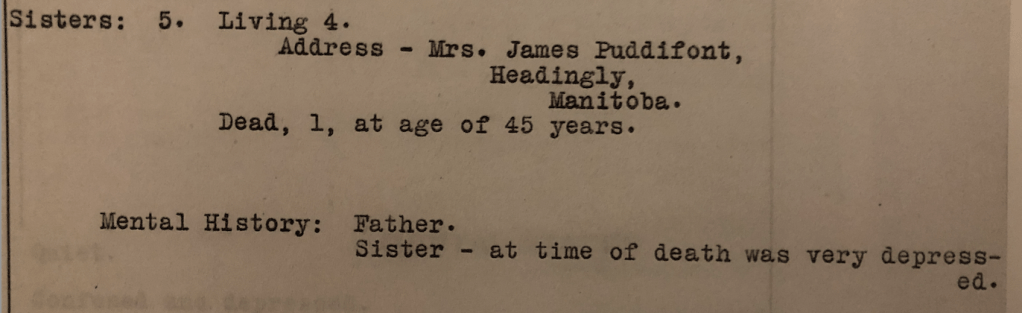

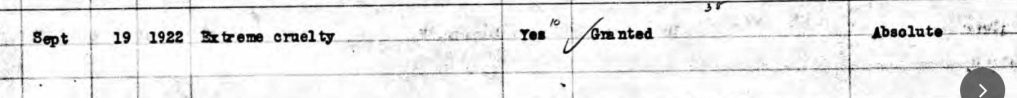

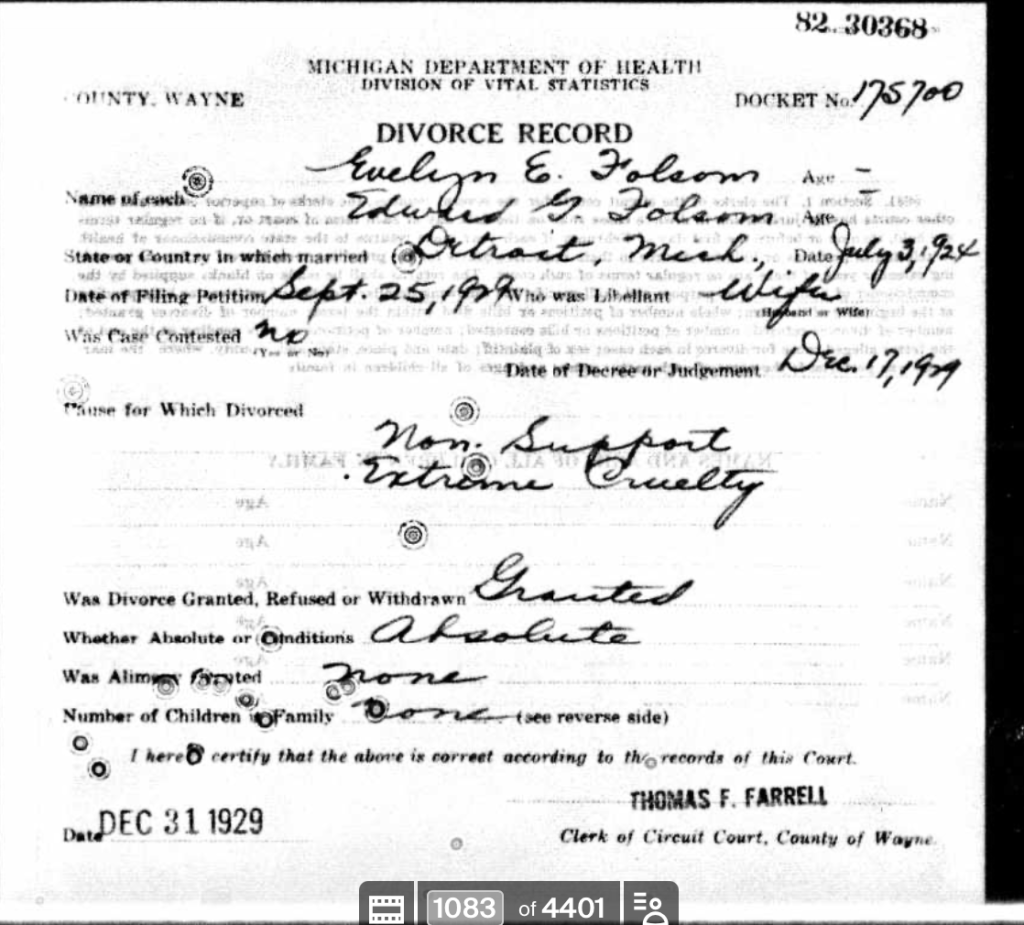

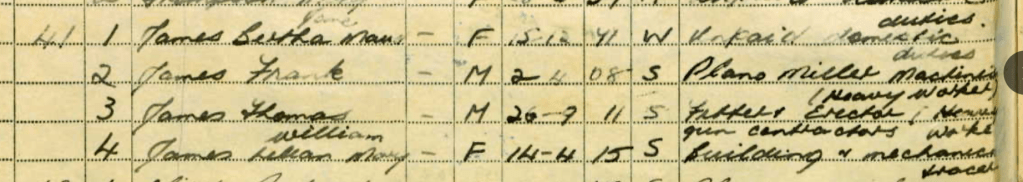

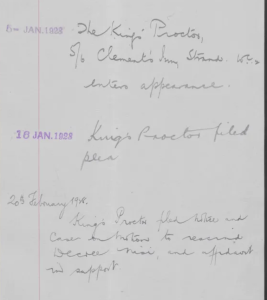

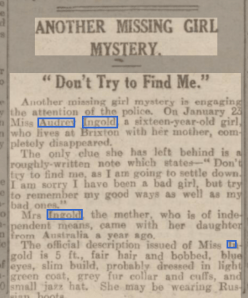

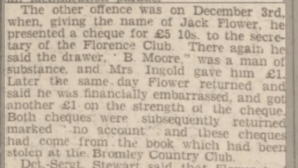

The lack of access to South African records makes it difficult to trace Harry’s further life in South Africa. After 1902, there is a 40 year gap in my research except for a few snippets:

- The 1906 Red Book South African city directory lists Harry as living in a suburb of East London, Eastern Cape and working as a clerk for the Cape Government Railway at Komgha Station.

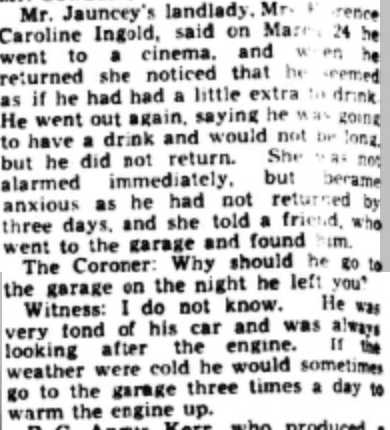

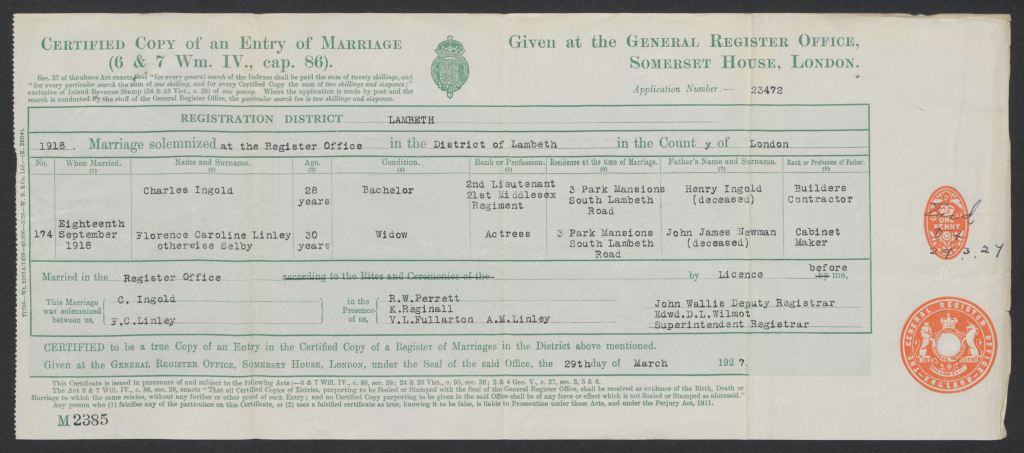

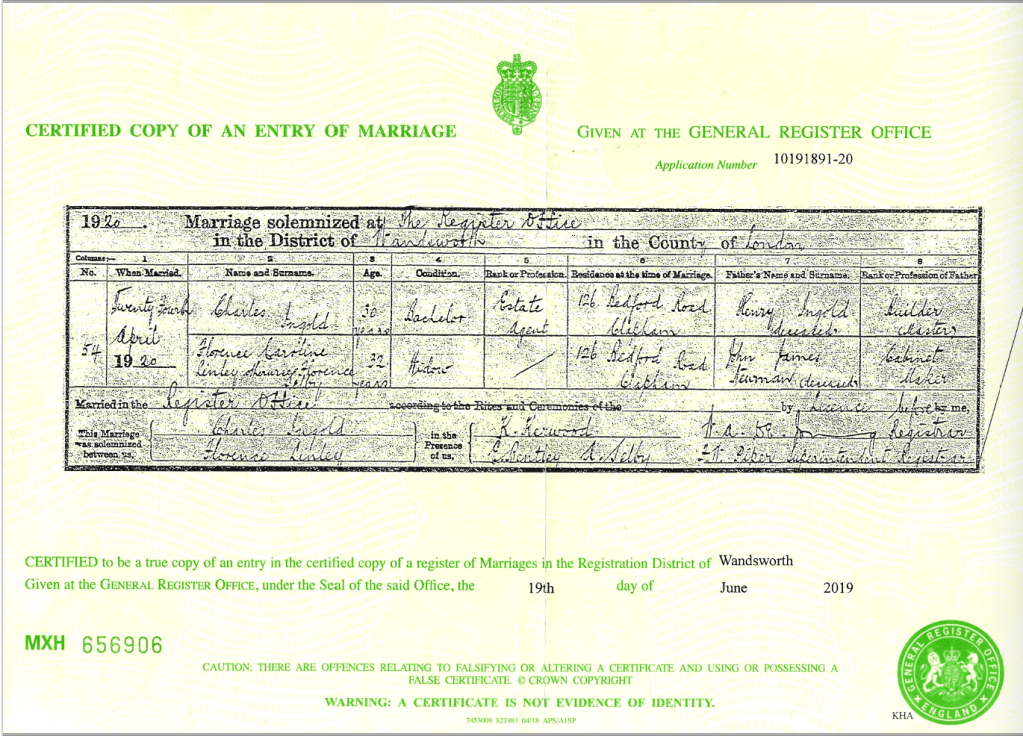

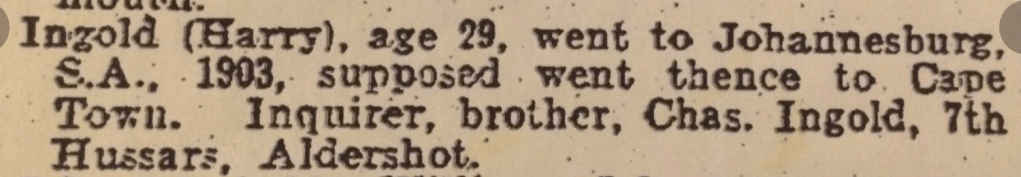

- On December 8, 1908 Charley Ingold, Harry’s youngest brother placed an ad in the London Echo. Charley was about to depart from England to South Africa as a Private with the 7th Hussars. I don’t know if the two ever connected again. Aside from getting the year wrong, Charley placed his ad in a show business newspaper….Charley is another story.

- On January 31, 1939, Harry James Ingold claims his Boer War Victory Medal 38 years after his service.

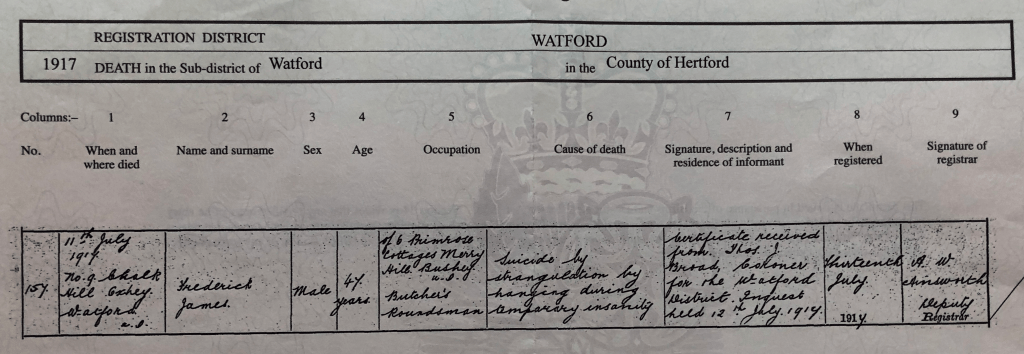

- On September 7, 2020, this death record popped up for me on FamilySearch.org Discoveries like this make many hours of tedious research worthwhile. There is no official record of a burial or tombstone.

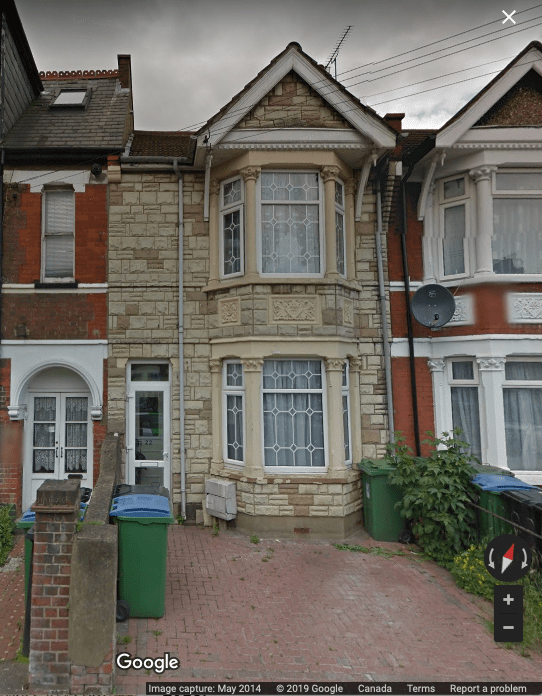

Below: Harry James Ingold’s last known address: 47 Longfellow Street, East London, SA. Note the bars on the windows and doors. South Africa is a dangerous place.

Below: East London is a tourist town today…

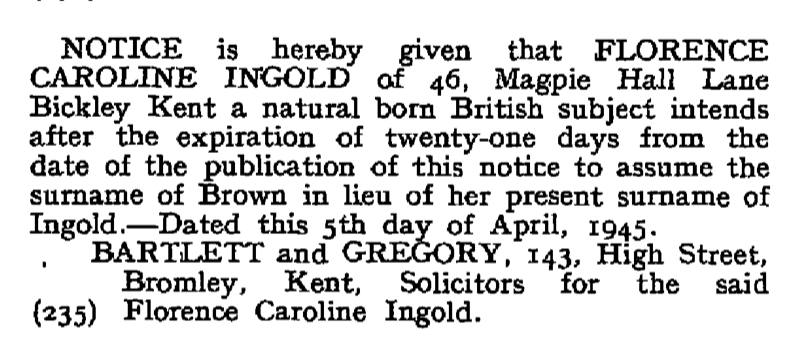

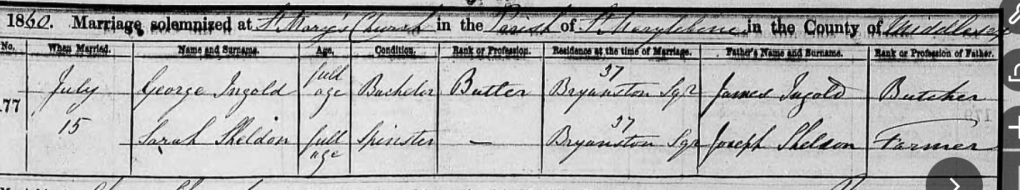

Marriage

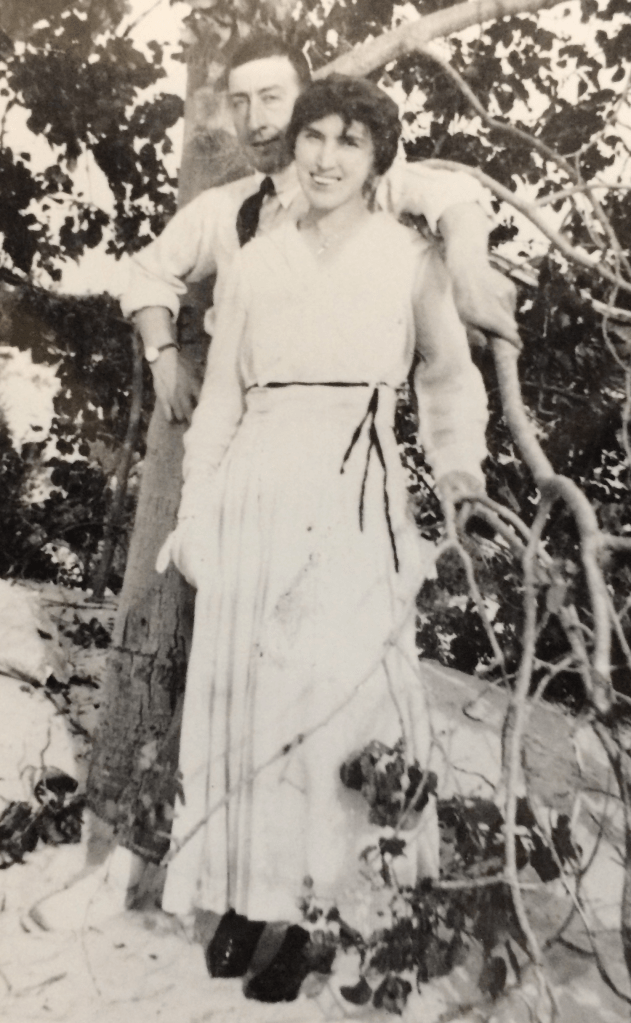

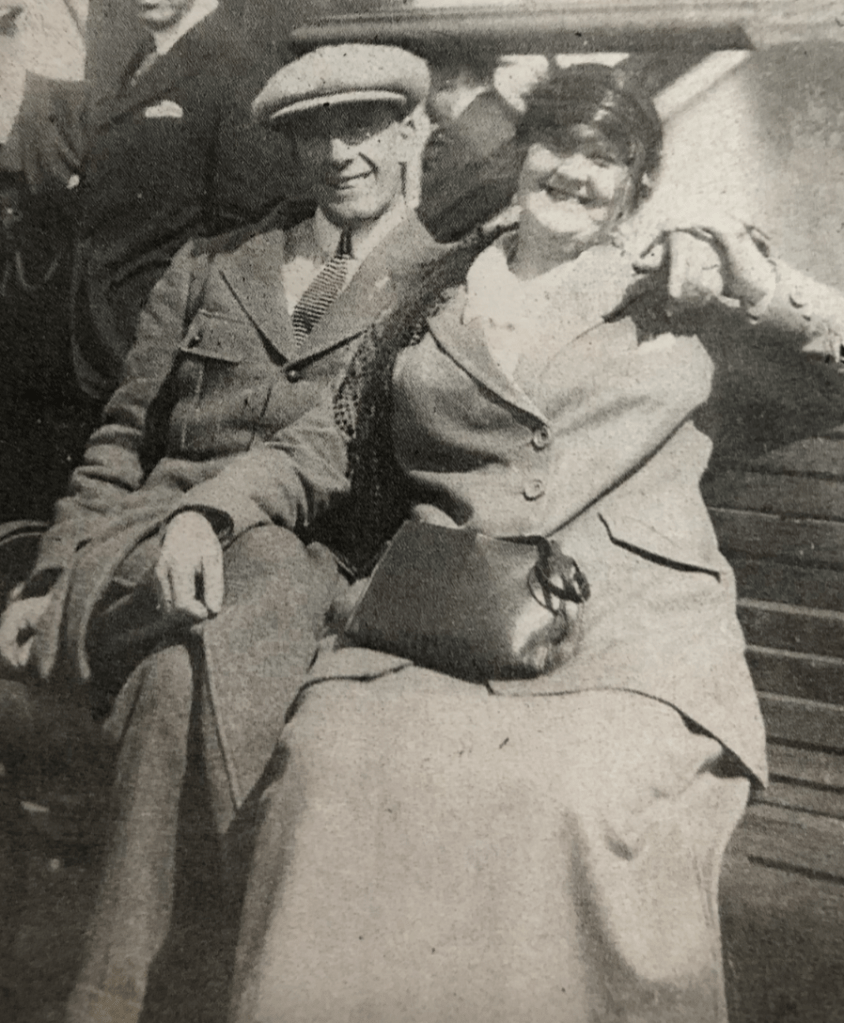

This photo was identified by a Puddifant cousin as Harry James Ingold. The lady in the photo is wearing a wedding ring, but every document in Harry’s name identifies him as single. There is a possibility the lady might be one of George’s sisters, Esther or Lilian, as they both married businessmen. That said, she does not look like an Ingold. For now, I will say this is not Harry James Ingold.

Below: Allegedly Harry James Ingold and alleged wife c. 1910.

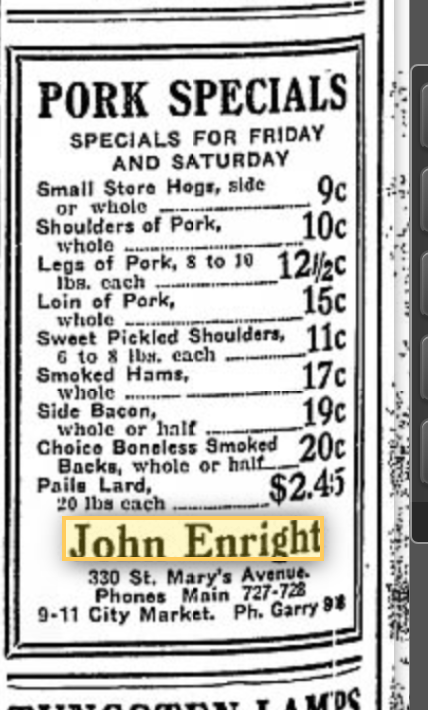

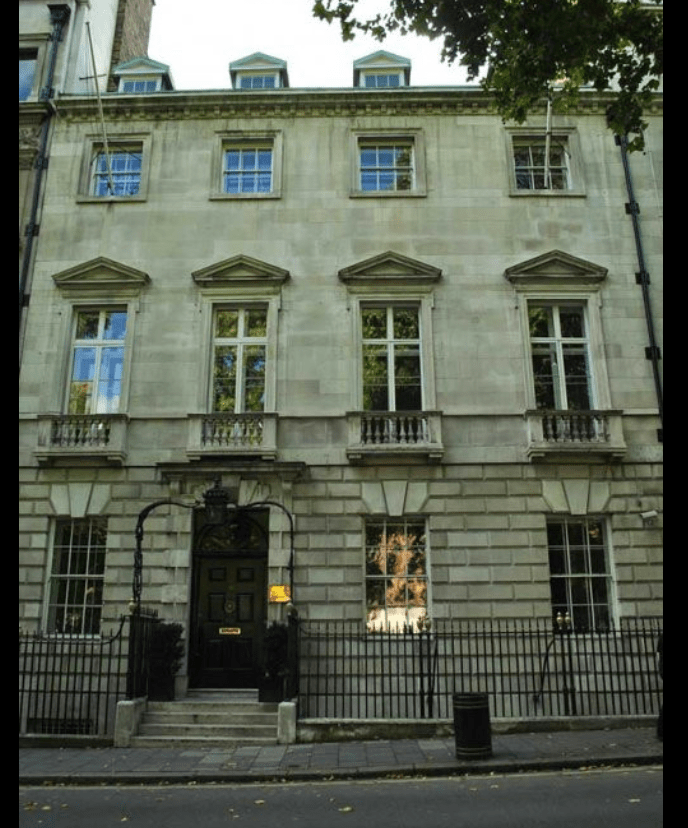

Late Life: “Caretaker at Tattersalls”

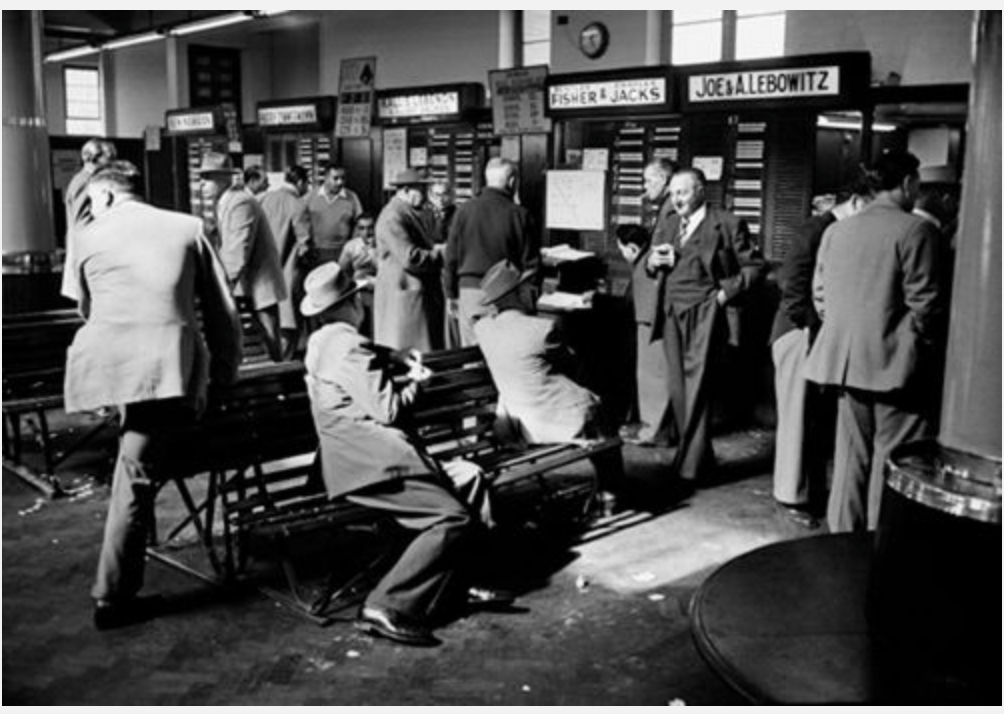

Since the 18th Century, Tattersalls has bred and auctioned race horses, as well as sponsoring prestigious races all around the world. In Harry’s time, Tattersalls operated a chain of betting shops throughout the country.

Below: Tattersalls Betting Shop in Johannesburg

I hoped for a better ending for Harry James Ingold, but his is a sad tale in the Ingold family: a young man with high hopes makes his way in a faraway land, but at the end of his life he’s sweeping floors and emptying ash trays in a bookie joint.

He should have stayed in England.